1.06 Troubleshooting

Christo Geoghegan

How to make a last-minute film about persecuted Jamaican youth living in a storm drain

Christo Geoghegan is an award-winning freelance documentary photographer, filmmaker and journalist. He has spent the past 12 years focusing his work on the impact of globalisation on the civil rights of fringe groups and societies.

In 2014, myself and director-producer Adri Murguia went to Jamaica to make a film with Kingston’s “gully queens” – a homeless group of gay and trans youth living in an open storm drain, known locally as a “gully”, next to an industrial estate. Initially, we’d intended to film a totally different documentary in Nigeria about straight medical workers who were helping smuggle HIV medication to gay people as it had recently become illegal, but this fell through. We’d had a budget approved and had a week to come up with a film, and Gully Queens was another pitch that Adri and I had put together with associate producer Adam Lilley. It wasn’t ready but we just had to run with it.

They were living in a storm drain..it’s not like they had emails we could contact them on.

There wasn't any way we could get in touch directly with any of the gully queens beforehand; they were living in a storm drain and it’s not like they had emails we could contact them on. But we spoke with Jamaican lawyer and activist Maurice Tomlinson regarding a rally he was staging in an attempt to push the government to overturn the Buggery Law – colonial-era legislation that outlaws anal sex, which is almost exclusively used to persecute gay people. Maurice was the only connection we had in a country we knew almost nothing about.

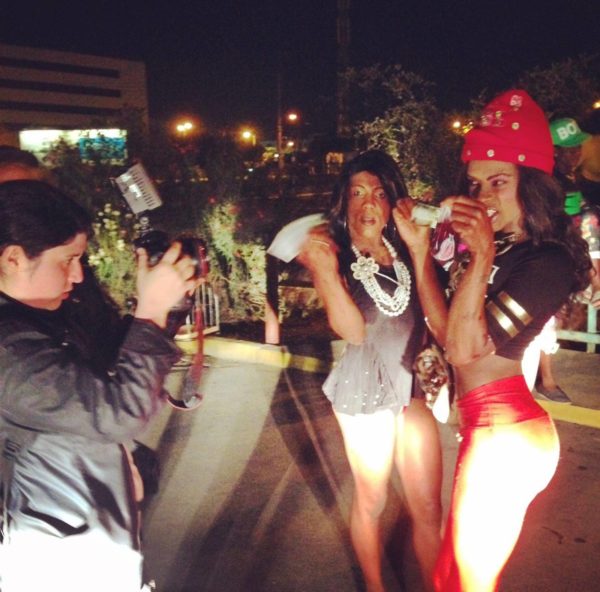

We arrived in Kingston the evening before, and within the first five minutes of shooting the film, I was standing in a busy traffic intersection in the middle of Kingston holding a rainbow flag as part of a group protest against LGBT+ discrimination in Jamaica. Jamaica is known for its virulent homophobia the world over, so this was a crash course in the situation there – we were heckled by drivers with shouts of “dirty batty boy” and the police were quickly on the scene, trying to shut us down. Shortly after that, we were properly introduced to the gully queens, who were living round the corner from the protest and taking part in it as well. When we first arrived at the gully it was quite tense, we had machetes wielded at us and some threats were made. But the gully queens are attacked on a daily basis, so they are used to being forced to defend themselves – any outsider, no matter where you’re from, is seen as a threat, and it's not hard to see why.

The gully queens were meant to be a subsection of the film but they ended up being the main focus of it, as their story was the most overt and the most untold. The film was very much a collaborative process and we wouldn’t have been able to do it without their help and input. We made a point of initially not shooting them for a while; we wanted to take our time to get to know them. They knew both me and Adri were gay which seemed to ease their mind a bit and we made sure they felt comfortable around us and the rest of the crew before we started rolling. They don’t tend to have people talking to them, asking them how they are – the only conversations they have with outsiders invariably end in conflict, so it took us a while to show them we weren’t going to do anything untoward, and just wanted to see the story from their perspective.

One of the most difficult things I guess is putting your emotions on pause.

Some of what they told us about their backgrounds was horrific and depressing, but they never lingered over that side of things too much. They weren’t victims themselves, they were victims of circumstance: they really made that obvious. Still, one of the most difficult things I guess is putting your emotions on pause – not to the point where you don’t empathise, because that’s really important when you’re making a film – but in terms of not getting swept away with the story, because you need to be able to leave the interpretation of its emotional subjectivity up to the viewer. You can make an emotional film without being emotional yourself throughout the process.

In the edit room, we were very conscious of not wanting the film to end up like torture porn.

The challenges didn’t stop once we got back to London. In the edit room, we were very conscious of not wanting the film to end up like torture porn; there had to be a balance where we showed the negative stuff they go through on a daily basis but also the humanity and sense of community that they’d created for themselves. It sounds easier than it was – we battled with the ending a lot, whether we wanted it to have an uplifting message at the end or a realistic one. I think we got there eventually.

Continue Module

Hard Yards:

Christo Geoghegan

How to make a last-minute film about persecuted Jamaican youth living in a storm drain

From the Brink:

Venezuela Rising

Alex Miller tells us what happened when he flew to Venezuela to cover the 2014 protests.

Show me the Money:

Daisy-May Hudson

The do’s and don’t’s of pitching at Sheffield Documentary Festival.